When Los Angeles Belonged to the Night

In the Los Angeles of memory and imagination, there exists a golden era when cars gleamed like spacecraft, neon painted the night in electric colors, and the city's wide boulevards promised endless possibility with every green light.

ART

5/1/20257 min read

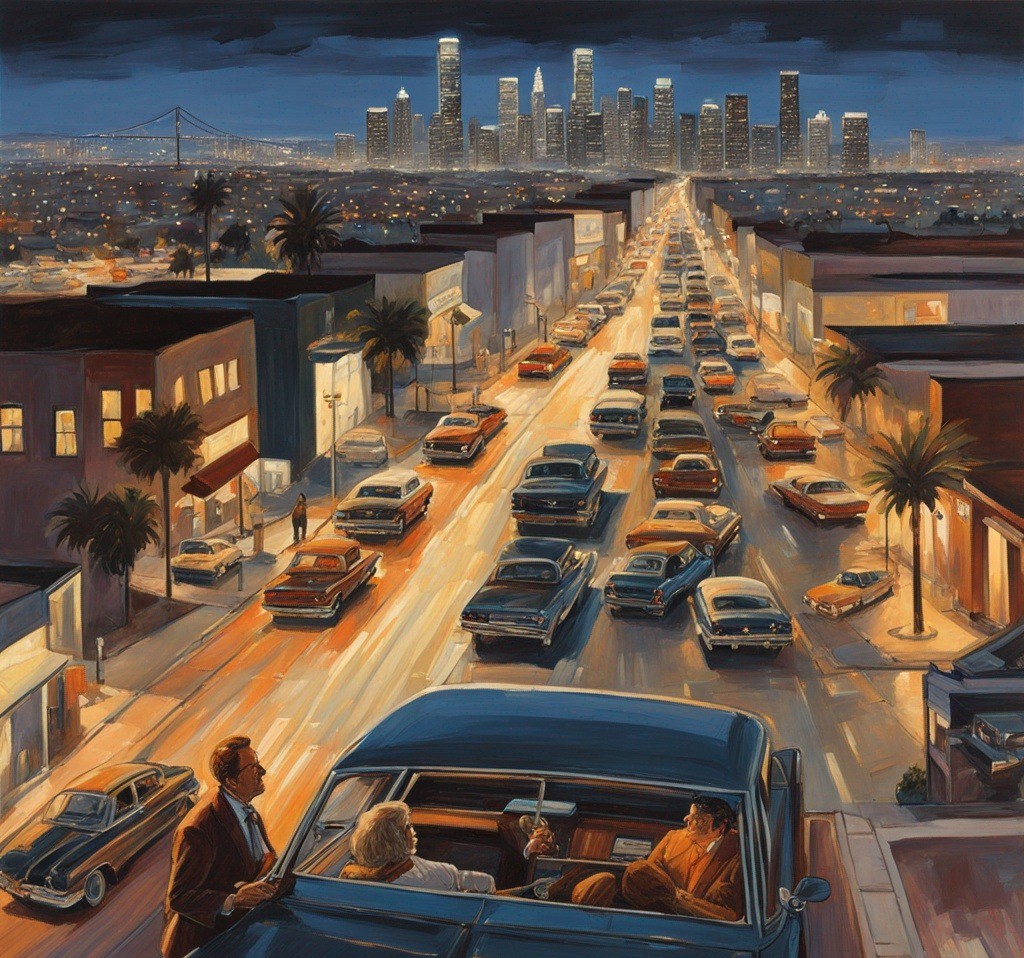

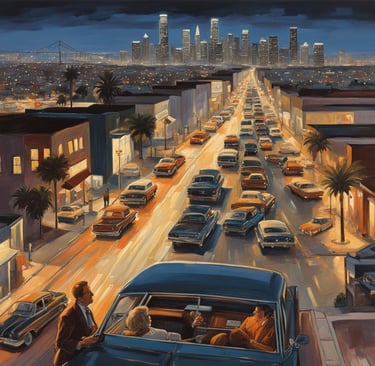

The photograph hangs in my grandfather's study—Los Angeles sometime in the mid-1960s, captured from above at dusk. The city's grid stretches toward distant mountains, hundreds of automobiles flowing along wide boulevards like luminous blood cells through the veins of some vast organism. In the foreground, a 1964 Chevrolet Impala dominates the frame, three passengers visible through its windows, faces turned toward a skyline still modest by today's standards but impressive for its time.

"That was the night we drove all over the city celebrating your grandmother's new job," my grandfather tells me whenever I ask about the image. "We felt like we owned Los Angeles that evening."

I've studied this photograph countless times, fascinated by the composition but even more by what it represents—a version of Los Angeles that exists now only in collective memory and artistic renderings. A city defined by automotive elegance, by the freedom of movement, by the particular magic of nightfall on wide streets lined with businesses announcing themselves in neon and incandescent glory.

This isn't just nostalgia. There was something genuinely distinctive about Los Angeles during this era that merits remembering, something that shaped not only how the city saw itself but how the world came to understand urban American life in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Los Angeles of the 1950s and 1960s represented the pinnacle of car culture—not merely as transportation but as a complex social ecosystem that influenced everything from architecture to romance, from music to dining habits. It was a time when automobiles weren't simply methods of getting from one place to another but extensions of identity, mobile living rooms that carried their occupants through the cinema-worthy backdrop of palm trees and neon-lit storefronts.

Unlike the traffic-choked freeways of contemporary LA, where cars represent confinement more often than freedom, the city's thoroughfares of this earlier era offered genuine pleasure in motion. Cruising wasn't just a teenage pastime but a legitimate form of entertainment—a way to see and be seen, to participate in the collective theater of urban life.

The cars themselves were marvels of design—rolling sculptures characterized by sweeping lines, abundant chrome, and unapologetic flourishes. They weren't engineered for efficiency but for impact. The towering tail fins of a Cadillac, the wide-mouth grille of a Buick, the perfect circularity of a Thunderbird's porthole window—these elements weren't mere transportation features but aspects of a design philosophy that valued expression over restraint, optimism over practicality.

But what made nocturnal Los Angeles truly magical during this era wasn't just the vehicles; it was the landscape they moved through. The city had embraced commercial architecture that was explicitly designed to be experienced from behind a windshield, at 35 miles per hour. Signs rose high above buildings to catch the eye of passing motorists. Restaurants shaped like hats or donuts or cameras announced their presence through form rather than just function. Gas stations featured soaring canopies that resembled flying saucers, their fluorescent lighting creating pools of intense brightness in the gathering darkness.

And then there was the neon—miles of hand-bent glass tubing filled with noble gases that transformed electricity into saturated color. Unlike today's LED-based signage, neon possessed a particular quality that felt alive, almost organic. Each sign was a custom creation, often designed and maintained by multi-generational family businesses. The soft red glow of a cocktail glass above a bar entrance, the animated blue ripple of a car wash sign, the warm yellow script announcing a family restaurant—these weren't just advertisements but landmarks, orientation points in the urban landscape.

In my grandfather's photograph, many of these signs are visible as bright points and streaks along the boulevards, their specific messages indecipherable at this distance but their collective effect unmistakable. They transform what might otherwise be an ordinary urban scene into something magical, cinematic, distinctly American.

This vision of Los Angeles—car-centric, horizontally expansive, defined by commercial rather than monumental architecture—represented a radical departure from traditional urban paradigms. Unlike the vertically oriented cities of the East Coast and Europe, with their emphasis on public spaces and pedestrian experiences, LA embraced the private automobile as its organizing principle. The city reimagined itself around the experience of movement rather than stasis, privileging flow over fixity.

Critics then and now have pointed to the problems this approach created—social isolation, environmental degradation, the transformation of public space into mere throughways. These criticisms have merit. But they sometimes overlook what this model offered: a democratized form of luxury, where ordinary middle-class families could experience the city as a panoramic spectacle from their private vehicles, enjoying levels of comfort and autonomy previously reserved for the wealthy.

My grandfather, a tool and die maker who never earned more than a modest income, speaks of how driving his Impala through nighttime Los Angeles made him feel like "a millionaire watching his estate." His car, purchased on an installment plan, granted him access to the entire city in a way that would have been impossible in more traditional urban environments.

"We'd drive down Wilshire Boulevard just to look at the buildings lit up at night," he recalls. "Or we'd head over to Van Nuys Boulevard on a Wednesday to watch the kids cruise in their hot rods. Sometimes we'd drive all the way to the beach just to smell the ocean for five minutes before heading back. The drive itself was the point."

This distinctly Los Angeles approach to urban life reached its apotheosis after dark. Nighttime transformed the city's sprawling, often architecturally unremarkable landscape into something extraordinary through the alchemy of artificial illumination. The darkness concealed the city's imperfections—the vacant lots, the utilitarian buildings, the accumulating smog—while highlighting its expressions of commercial optimism and individual freedom.

Hollywood understood this instinctively, incorporating nocturnal Los Angeles into countless films as both setting and character. From the moody noir of the 1940s to the neon-saturated dreamscapes of 1980s music videos, filmmakers recognized that Los Angeles at night possessed a visual grammar unlike any other American city—simultaneously glamorous and gritty, expansive yet intimate, familiar but always slightly unreal.

Much of this Los Angeles has disappeared now, erased by changing economics, evolving tastes, and shifting civic priorities. The grand movie palaces that once lined Broadway downtown have been converted to retail spaces or churches. The distinctive coffee shops with their Googie architecture—those angular, atom-age structures that seemed to defy gravity—have largely been replaced by generic fast-food outlets. The neon has given way to LED displays, trading character for energy efficiency.

Even the automotive experience has fundamentally changed. The freedom of movement that defined earlier eras has been constricted by population growth, with the average Los Angeles driver now spending over 100 hours annually stuck in traffic. The cars themselves, while technologically superior in every measurable way, have lost the distinctive personality that made vehicles of the 1950s and 1960s rolling expressions of American optimism and individuality.

But traces of this earlier Los Angeles persist if you know where to look. On certain stretches of Sunset Boulevard or Ventura Boulevard, restored neon signs still cast their distinctive glow. At Bob's Big Boy in Burbank, classic car enthusiasts gather every Friday evening to display their meticulously maintained vehicles, creating a temporary time capsule in the restaurant's parking lot. The Petersen Automotive Museum on Wilshire Boulevard preserves both the vehicles and the cultural context that made Los Angeles the epicenter of car culture.

And then there are the films, photographs, and paintings that capture this vanished Los Angeles—works of art that through careful composition and selective focus distill the essence of what made the city's nocturnal landscape so compelling. Edward Hopper's "Nighthawks," though set in New York, captures the particular quality of urban solitude illuminated by artificial light that defined Los Angeles after dark. Julius Shulman's architectural photographs, especially his famous shots of modernist homes overlooking the city at night, document the dream of Los Angeles as a place where even middle-class residents could live with one foot in urban civilization and the other in the cosmos.

Contemporary artists continue to explore this territory, recognizing that something essential about American identity was expressed in the Los Angeles of this era. The paintings of Eric Fischl, the photographs of Philip-Lorca diCorcia, the films of Michael Mann—all engage with the particular quality of artificial light in nocturnal urban settings, the way it transforms ordinary scenes into stages for human drama.

There's a word in Japanese—"mono no aware"—that describes the pathos of things, the gentle sadness that comes from recognizing the impermanence of everything in life. I feel this when I look at my grandfather's photograph, knowing that the Los Angeles it depicts exists now primarily in cultural memory and artistic representation rather than physical reality.

But there's also something hopeful in this recognition. Cities are never static entities but rather ongoing conversations between human intention and historical circumstance. The Los Angeles of gleaming automobiles cruising neon-lit boulevards may have largely vanished, but its essential spirit—the embrace of mobility, the democratization of luxury, the transformation of the mundane into the magical through light and movement—continues to influence how we imagine urban possibility.

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to this vanished Los Angeles isn't mere nostalgia but rather a commitment to preserving what made it special—not just in museums and archives but in our approach to urban life. This might mean protecting the remaining examples of Mid-Century commercial architecture, maintaining the historic neon signs that still announce neighborhood landmarks, or simply taking the time occasionally to experience the city at night from behind the wheel, moving through the grid of lights with no particular destination in mind.

As my grandfather puts it, "The Los Angeles I knew wasn't perfect, but at night, with the windows down and good music on the radio, it sure felt like it could be."

In a city built on dreams, sometimes the most powerful ones are those we've already lived—golden moments captured in photographs and memories, illuminated by neon that no longer exists but still somehow lights our understanding of what a city can be when night falls and the boulevard stretches endlessly before us.

Get in touch