Golden Hour in Vintage London

The Lost Art of Street Café Culture

ART

5/7/20259 min read

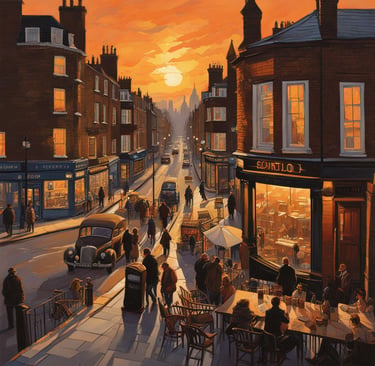

There's a distinctive magic that occurs when sunlight tilts toward evening, painting everything it touches with a golden-amber glow. Photographers call it the "golden hour" – that brief window when shadows lengthen, light softens, and even the most ordinary scenes transform into moments of extraordinary beauty. The painting that inspires this reflection captures precisely such a moment: a London street café bathed in sunset light, sometime in what appears to be the 1940s or early 1950s.

A Canvas of Light and Memory

The scene before us presents a quintessentially British tableau. A narrow street lined with shops climbs gently uphill, their windows glowing with interior light that competes with the magnificent sunset. Pedestrians navigate the pavement, some pausing at storefronts, others purposefully striding toward unknown destinations. A classic automobile – possibly a Humber or early Rover – sits parked alongside the narrow road, its curved fenders and elegant profile a testament to an era when cars were designed with artistry rather than wind tunnels.

But it's the café that draws our eye. Patrons sit at simple wooden tables beneath a modest awning, newspapers spread before some, drinks at their elbows, conversations flowing. The magic of the painting lies in how the setting sun bathes everything in that extraordinary golden light, creating long shadows that stretch across the pavement, turning an everyday scene into something timeless and poignant.

The Rise and Evolution of British Café Culture

To understand what we're seeing in this nostalgic image, we should trace the evolution of café culture in Britain – a tradition that differs markedly from its continental counterparts.

Unlike Paris or Rome, where café society had deep historical roots, Britain came late to the concept of leisurely public dining and drinking. The traditional British pub had, of course, existed for centuries, but these were primarily masculine domains focused on ale and spirits. Tea houses catered to a more genteel crowd but maintained strict social conventions.

The modern café as we understand it – a casual establishment serving food and beverages where patrons might linger for conversation – emerged in Britain during the interwar period, inspired partly by continental examples but adapted to British sensibilities. Their growth accelerated after World War II, particularly in London, where a population hungry for normalcy and small pleasures embraced these informal gathering spaces.

The post-war period depicted in our painting marked a fascinating transitional time. Rationing was still in effect (it wouldn't fully end until July 1954), and Britain was navigating the complex realities of its diminished global role. Yet amid these challenges, a new urban social life was emerging – one where rigid class distinctions, while still present, were gradually loosening.

Street cafés like the one in our image represented something quietly revolutionary: public spaces where various social classes might intermingle, where women could comfortably sit alone, and where conversation flowed freely among strangers. They became theaters of everyday life – places to see and be seen, to exchange ideas, or simply watch the world go by.

The Theater of the Street

What makes street cafés particularly fascinating is their liminal nature – they exist at the threshold between private and public space. Sitting at an outdoor café table, one is simultaneously participant and spectator in the urban drama.

Our painting captures this duality perfectly. We see both the café patrons engaged in their conversations and the passing parade of city life beyond them. Some figures stand at the boundary between these worlds, perhaps deciding whether to join the seated crowd or continue their journey.

The street itself functions as a kind of stage. Notice how the artist has composed the scene to capture multiple layers of urban life: the immediate foreground of café tables, the middle ground of pedestrians and automobile, and the background suggesting more shops, buildings, and the warm glow of distant windows. This layering creates a depth that invites the viewer to imagine narratives extending beyond the frame.

The vintage car deserves special mention, as it anchors the image firmly in its historical moment. Automobile ownership was still relatively uncommon in post-war Britain, and the presence of this handsome vehicle signals something about the neighborhood and era. It's neither an ostentatious luxury car nor a utilitarian vehicle, but rather a solid middle-class conveyance – perhaps belonging to a doctor, solicitor, or successful shopkeeper.

Light as Character

The true protagonist of this painting, however, is light itself. The setting sun creates a theatrical effect, turning windows into glowing rectangles and casting long, dramatic shadows across the pavement. This isn't merely aesthetic choice – it's psychological storytelling.

Golden hour light evokes a complex emotional response. There's warmth and beauty, certainly, but also a subtle melancholy – the awareness that this perfect light is fleeting, already beginning to fade even as we appreciate it. It's no coincidence that so many painters and photographers are drawn to this time of day; it naturally layers emotion onto whatever scene it illuminates.

In our café painting, the sunset light performs multiple functions. It unifies the composition by washing everything in similar tones. It creates dramatic contrasts between illuminated surfaces and shadows. And perhaps most importantly, it infuses an otherwise ordinary scene with a sense of significance – suggesting that these everyday moments, these casual conversations among anonymous people, contain their own kind of quiet magnificence.

Conversation and Community

What were they discussing, these café patrons caught in amber light? The painting dates to an extraordinary period in British history – the aftermath of global war, the beginning of the Cold War, the early years of the welfare state, the decline of empire, and the first stirrings of what would become youth culture.

Perhaps they debated politics – the policies of Clement Attlee or Winston Churchill (depending on the exact year). Maybe they discussed the nationalization of industries or the creation of the National Health Service. Some might have talked about rebuilding efforts in London, still visibly scarred from the Blitz. Others might have shared more personal concerns – family matters, workplace frustrations, romantic entanglements.

Whatever their conversations, these café gatherings represented something vital: the maintenance of civil society through face-to-face interaction. Each table formed a temporary community, a space where ideas could be exchanged, relationships maintained, and the social fabric strengthened through the simple act of shared presence.

The Economics of Ambiance

While we might romanticize the café depicted in our painting, it's worth considering the economic realities behind such establishments. Running a café has always been a precarious business, balancing thin margins against the need to create an environment where people wish to linger.

The post-war period brought particular challenges. Food and drink were still subject to rationing restrictions, limiting what could be served. Materials for repairs and improvements were scarce. Fuel for heating was expensive and sometimes restricted. Labor costs were rising as Britain moved toward a more equitable economic system.

Yet despite these constraints, café owners understood something crucial: they weren't merely selling coffee, tea, or simple meals – they were selling atmosphere, experience, and social connection. The wooden chairs, the modest tables, the small awning in our painting might appear humble, but they created a setting where people could participate in public life while enjoying small comforts.

This understanding – that cafés traffic in intangible goods as much as physical ones – helped sustain such establishments even through economic hardship. Patrons might economize in many areas of life, but the modest expense of a cup of tea or coffee in exchange for an hour in pleasant surroundings often remained an affordable luxury.

The Urban Rhythms

The street depicted shows signs of a neighborhood commercial district rather than a main thoroughfare or tourist area. The shops appear to be practical rather than luxury establishments, suggesting a middle-class or upper-working-class area. Such neighborhoods followed distinct daily rhythms that would have been familiar to any urban dweller of the era.

Mornings would bring shopkeepers raising their shutters, delivery vehicles bringing fresh goods, and early customers on their way to offices or other workplaces. Midday would see a lunchtime rush, perhaps factory or office workers taking brief respites from their labors. Afternoons might be quieter, with retired individuals or mothers with young children forming the main clientele.

But it's the evening scene captured in our painting that holds particular significance. This transitional time – not quite workday, not quite night – created a unique social opportunity. Workers heading home might stop for a brief refreshment. Couples might meet after their respective workdays. Neighbors might exchange news before heading to their evening meals.

The golden hour thus corresponded to a social golden hour – a brief window when various elements of urban society converged, creating a particularly rich tapestry of interaction.

The Lost Art of Watching

Perhaps what's most striking about our café scene to contemporary eyes is the absence of something we now take for granted: electronic devices. No one stares at a smartphone screen. No laptops glow on tabletops. No earbuds isolate individuals from their surroundings.

Instead, we see people engaged in three activities that have become increasingly rare: conversing directly with companions, reading physical newspapers or books, or simply watching the street scene before them. This last activity – what we might call the art of watching – deserves particular attention.

Before endless digital distractions became available, observing one's surroundings constituted a legitimate form of entertainment and education. Café patrons would study passersby, noting their clothing, mannerisms, and interactions. They would absorb the architectural details of buildings, the changing quality of light, the patterns of traffic and commerce. This wasn't mere idleness – it was a form of direct engagement with one's environment, a way of reading the urban text.

Writers, artists, and creative thinkers have long understood the value of such observation. The novelist Virginia Woolf, writing some years before our painting's era, described the creative nourishment she derived from London streets: "To walk alone in London is the greatest rest." Philosopher Walter Benjamin developed an entire conceptual framework around the flâneur – the urban observer who reads the city as others might read a book.

Our café scene captures this observational culture at its most natural. Some patrons converse, others read, but many simply watch – absorbing the theater of everyday life with an attentiveness that now seems almost foreign.

Preserving Memory Through Art

Why does this painting – a simple street scene from decades ago – resonate so deeply with contemporary viewers? Beyond its aesthetic qualities, I believe it serves as a powerful memento of sociability patterns we recognize as increasingly endangered.

The digital revolution has transformed how we interact with urban space and with each other. Modern café-goers often sit in physical proximity while remaining mentally elsewhere, their attention captured by distant concerns delivered through glowing screens. The art of watching has been supplanted by the habit of scrolling. Conversation with strangers has become rarer, replaced by interaction with known entities through social media platforms.

None of this is to suggest a simplistic narrative of decline. Today's digital café culture enables connections impossible in earlier eras and offers its own forms of community and exchange. Yet something has undeniably been lost – something captured with poignant clarity in our sunset painting.

Art preserves what photography sometimes cannot: not just the visual reality of a moment, but its emotional tenor, its atmospheric qualities, the way it felt to be present in that time and place. Through the artist's selective emphasis, we experience not just how the scene looked, but how it mattered.

Finding Our Way Back

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of artworks like our café painting is how they remind us of pleasures and practices still available to us, albeit in modified form. The sunset still creates golden hour light. Cafés still offer respite from private isolation. Conversation remains our most profound form of connection. The theater of the street continues its endless performance.

The painting serves not just as a record of what has passed, but as an invitation to what remains possible. We can still choose to sit without digital distraction, to observe our surroundings with attentiveness, to engage with the strangers who share our urban spaces. We can still appreciate the transformative quality of evening light, the simple pleasure of a beverage enjoyed in public company, the rich text of city life awaiting our reading.

In a world increasingly mediated through screens, such direct experiences take on new significance. They ground us in physical reality, in the sensory richness of embodied existence, in the complex social ecosystem we inhabit but often fail to notice.

Conclusion: The Eternal Moment

What ultimately makes our café painting so compelling is how it captures both historical specificity and timeless human constants. The clothing styles, the automobile, the architectural details belong to a particular moment in London's evolution. But the human activities depicted – gathering, conversing, observing, sharing space – represent enduring patterns of social behavior that connect us directly to these anonymous figures from decades past.

The golden light that bathes the scene serves as a perfect visual metaphor for this tension between transience and permanence. Like the sunset itself, the particular moment depicted could not last – yet sunsets themselves are eternal, recurring in endless variation as long as our planet turns.

Similarly, while the specific café may long since have disappeared, and its patrons passed into memory, the human impulse to gather, to share, to witness, and to belong continues unabated. New generations find their way to public tables, order their preferred beverages, and participate in the ongoing conversation of urban life.

In that sense, though we may never know their names or stories, the café patrons in our golden-hour painting are not truly anonymous. They are us – earlier participants in the same social dance we continue today, caught in a perfect moment of connection, community, and fleeting beauty. And through the artist's vision, that moment achieves a kind of immortality, inspiring us to look more closely at our own golden hours, so easily overlooked, so worthy of attention.

Get in touch